By Gilla Everdine

Resilience in the Classroom: How Schools Persist Amidst Conflict and Displacement in Bamenda, North West Region, Cameroon

Even within modest classrooms constructed from mud blocks, where students diligently balance their exercise books on makeshift desks, the presence of learning is a testament to resilience. The echoes of a protracted conflict have irrevocably reshaped daily life, and despite the devastating reality of burnt down schools, the pursuit of education continues.

For eight years, insecurity in Cameroon’s North West Region has forced the closure of thousands of schools, displaced entire families, and disrupted the educational trajectory of a generation.

Yet, with unwavering determination, students and parents bravely navigate these odds, prioritizing their children’s future by ensuring their access to education. Education stakeholders, community members, and teachers alike are continuously innovating to sustain learning, even under the most precarious circumstances.

The escalation of conflict in the North West Region has profoundly impacted educational institutions. Numerous schools have been shut down, others reduced to ashes by violence, and many have been abandoned as teachers face perilous situations, including kidnappings and killings. This widespread insecurity has compelled families to seek refuge in safer areas, forcing them to rebuild their lives from scratch.

The COVID 19 pandemic further exacerbated these challenges, deepening existing learning gaps and intensifying the risk of school dropouts. This global health crisis accelerated a paradigm shift in learning, pushing towards digitalization and remote educational solutions. As remarked by Mr. Nfor Richard, Sub Director of General Affairs, at the Delegation of Secondary Education, Northwest Regional, says “Education became one of the silent casualties of the crisis. Children lost not only classrooms but also structure, protection, and hope.”

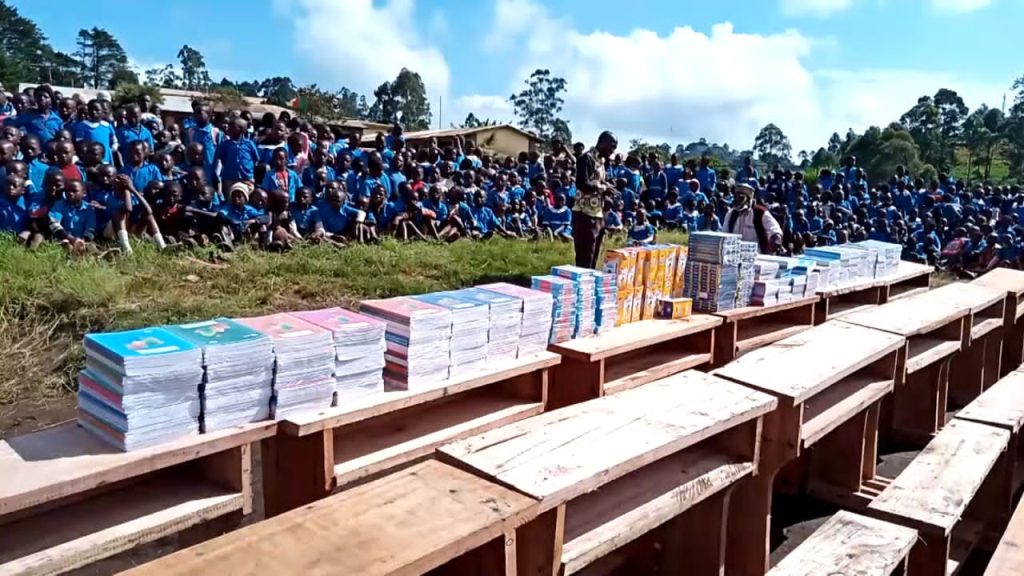

In response to this crisis, communities across the North West Region have spearheaded the establishment of informal and community based learning centers. These vital spaces, often hosted in unaffected schools like Our lady of Lourdes and PSS Mankon, or community and church halls, provide displaced children with access to fundamental education in relatively secure environments. Volunteer teachers from nearby Divisions many of whom are themselves displaced, are the backbone of these initiatives.

Despite often receiving irregular or no salaries, they are driven by a profound sense of duty. Mr David Martha, a former primary school teacher in Wum now working in a community learning center, articulates this commitment: “I could not watch these children roam the streets without learning. Teaching gives them a sense of normalcy, even when everything else feels uncertain.”

During periods of heightened insecurity and pandemic related restrictions, alternative learning methodologies gained significant traction. Online (internet based) lessons, printed self-study materials, and small group tutoring emerged as crucial tools to bridge the Educational divide, particularly in remote and high risk areas.

Despite these commendable efforts, substantial obstacles persist. Limited funding, a critical shortage of qualified teachers, the profound psychological trauma experienced by learners, and inadequate infrastructure continue to impede effective education delivery.

A statistics of about 12,980 total births were recorded at the Bamenda Regional Hospital from (2018–2022) As Girls, in particular, face amplified risks of early child labor, and permanent school dropout. Evidence of this alarming trend emerged in 2018, with a notable increase of 24 % adolescent girls (aged 15–19) have already begun bearing childbirths among girls presenting at the Regional hospitals. Mr Nfor Richard an Educational experts caution that without sustained investment, the region faces dire long term social and economic ramifications.

As a fragile calm gradually returns to some communities, the slow process of school reopening has begun. However, the invaluable lessons learned during years of disruption are now shaping a more adaptable and resilient educational approach. This future model integrates formal schooling with robust community engagement and comprehensive emergency preparedness strategies. For displaced learners like Ngum Angel from Yaounde, a 21 year old, returning to her home region signifies a profound personal victory. “When I am in class,” she shares softly, “I feel like my future is still possible.”

In the North West Region, the continuation of education is not a concession to hardship, but a powerful refusal by communities to allow conflict and crisis to define their children’s destiny. Their embrace of development is evident in the ongoing reconstruction of classrooms across villages and communities, symbolizing a steadfast commitment to a brighter future.